I. INTRODUCTION

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

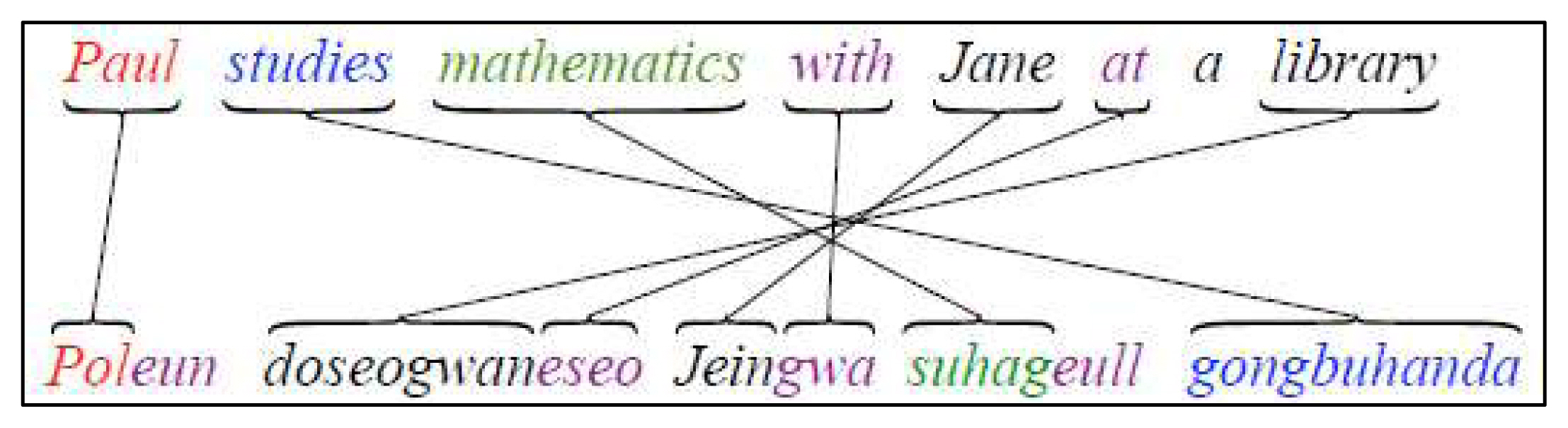

1. Korean Morphological Analysis

2. POS Tagging

Separating a word-phrase into morphemes;

Recovering the original form for changed phonemes;

Tagging the POS to each morpheme (Nguyen et al., 2019, p. 414)

3. Differences Between Languages

Korean (SOV): Gene-i hakgyo-e gass-da.

English (SVO): Gene went to school.

English Error: Gene went school. (Adapted from Shaffer, 2002, p. 221)

Among the content or function words in English, which has more errors?

Which has the most frequent errors among seven division (N, V, M, I, J, E, X) in Korean?

What are the common errors among josa or eomi in Korean?

III. METHOD

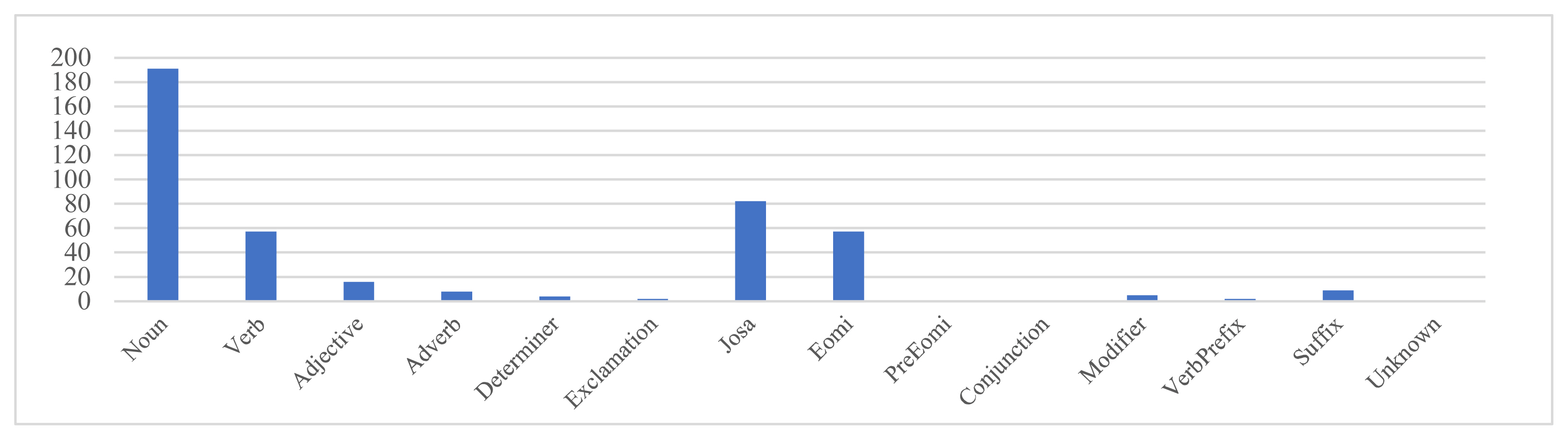

parsing English subtitles by the POS tagger, which reads English text and tags parts-of-speech to each word, such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives. The POS tagger is a natural language parser program that analyzes the grammatical structure of sentences and is called the Stanford Log-Linear Part-Of-Speech Tagger. The data were analyzed and categorized into 31 groups by tagging the parts-of-speech: DT, RP, CD, NN, NNS, NNP, NNPS, EX, PRP, PRP$, POS, RBS, RBR, RB, JJS, JJR, JJ, MD, VB, VBP, VBZ, VBD, VBN, VBG, WDT, WP, WP$ WRB, TO, IN, and CC. This categorization is included in the Appendix. The Korean subtitles were first processed in Openkoreatext, an open-source Korean text processor that handles Korean normalization and tokenization. It is categorized into 14 groups by tagging the parts-of-speech: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, determiners, exclamations, josa, emoi, preeomi, conjunction, modifier, verb prefix, and suffix. Next, we require a more detailed and specified analyzer in terms of postpositional particles such as josa or eomi.

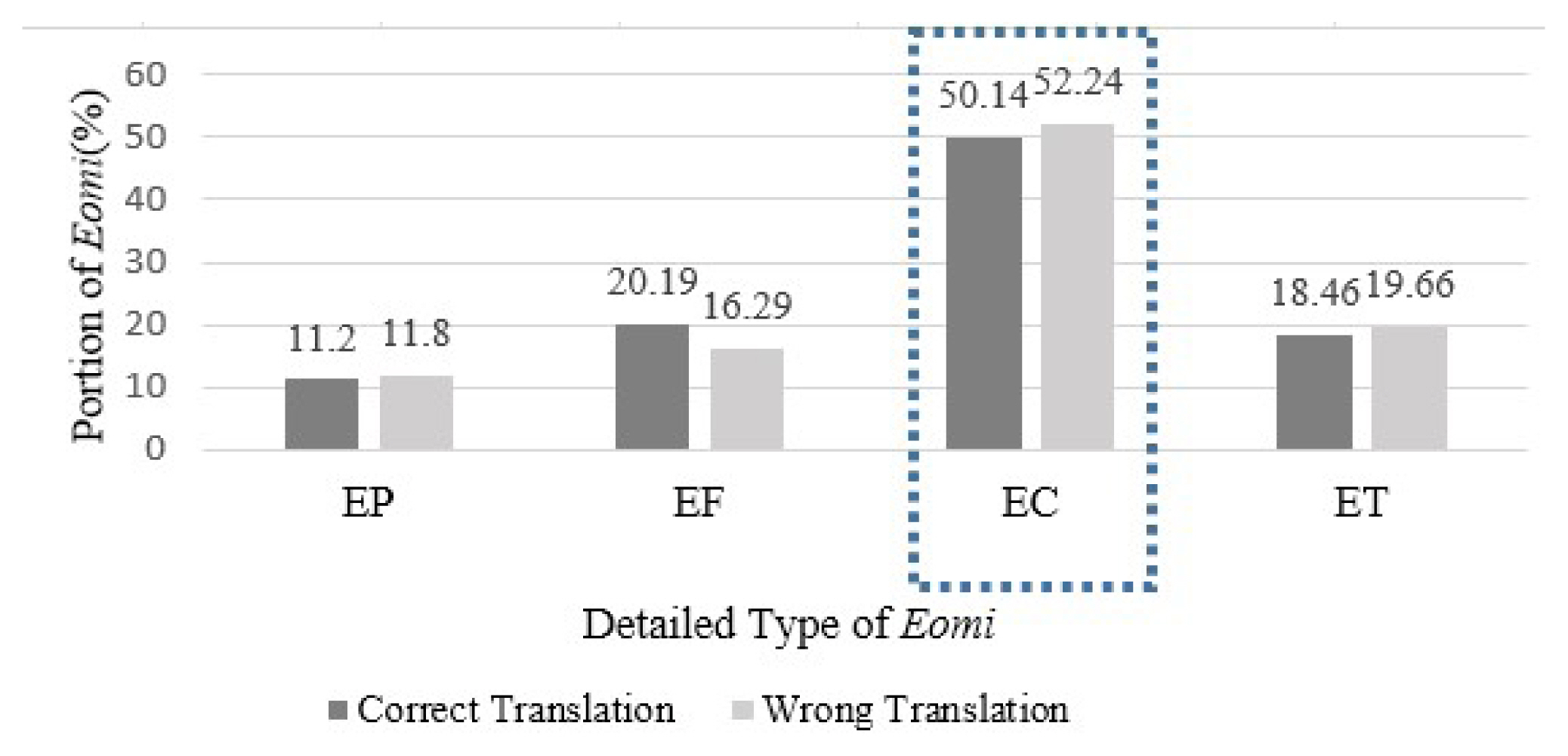

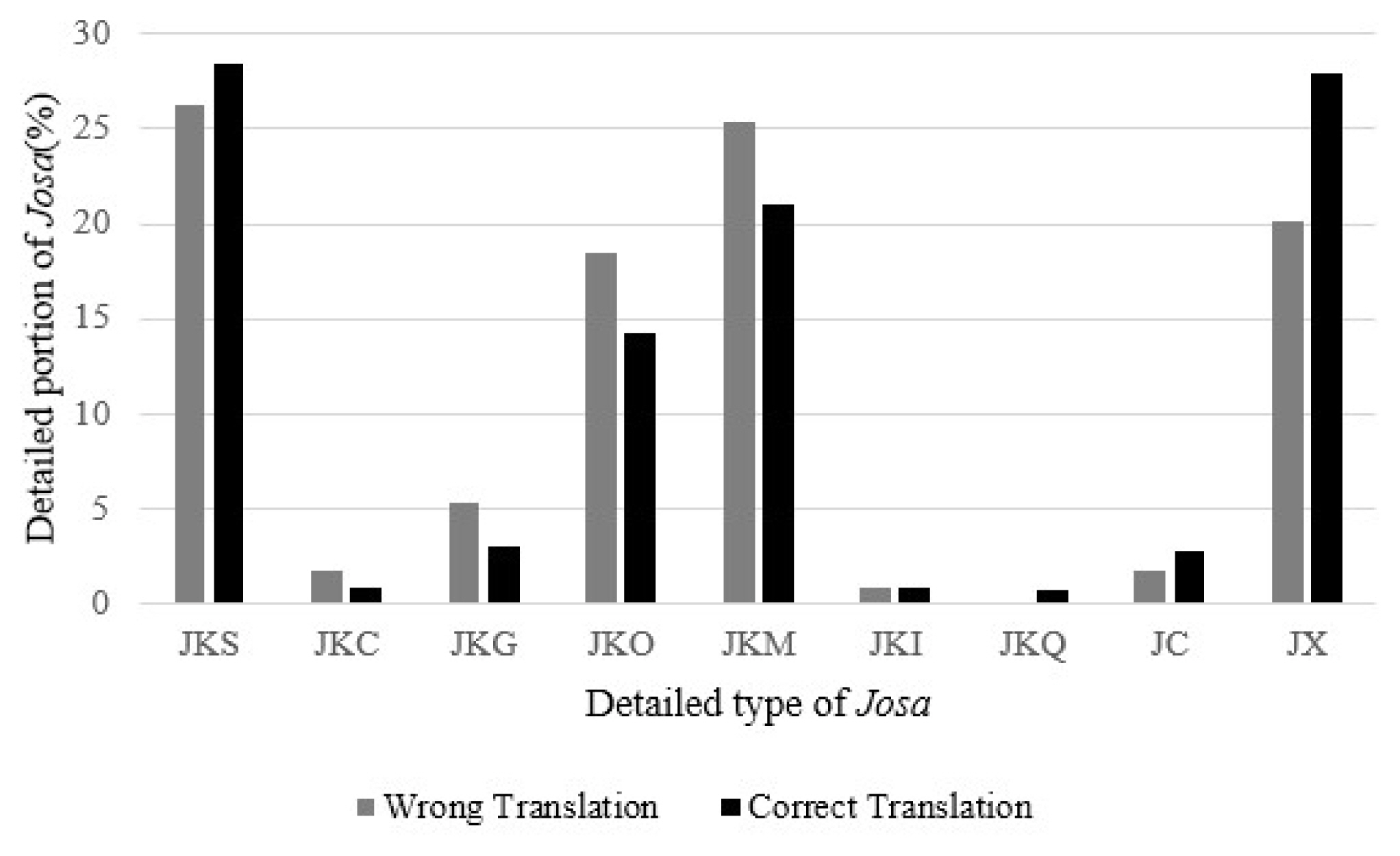

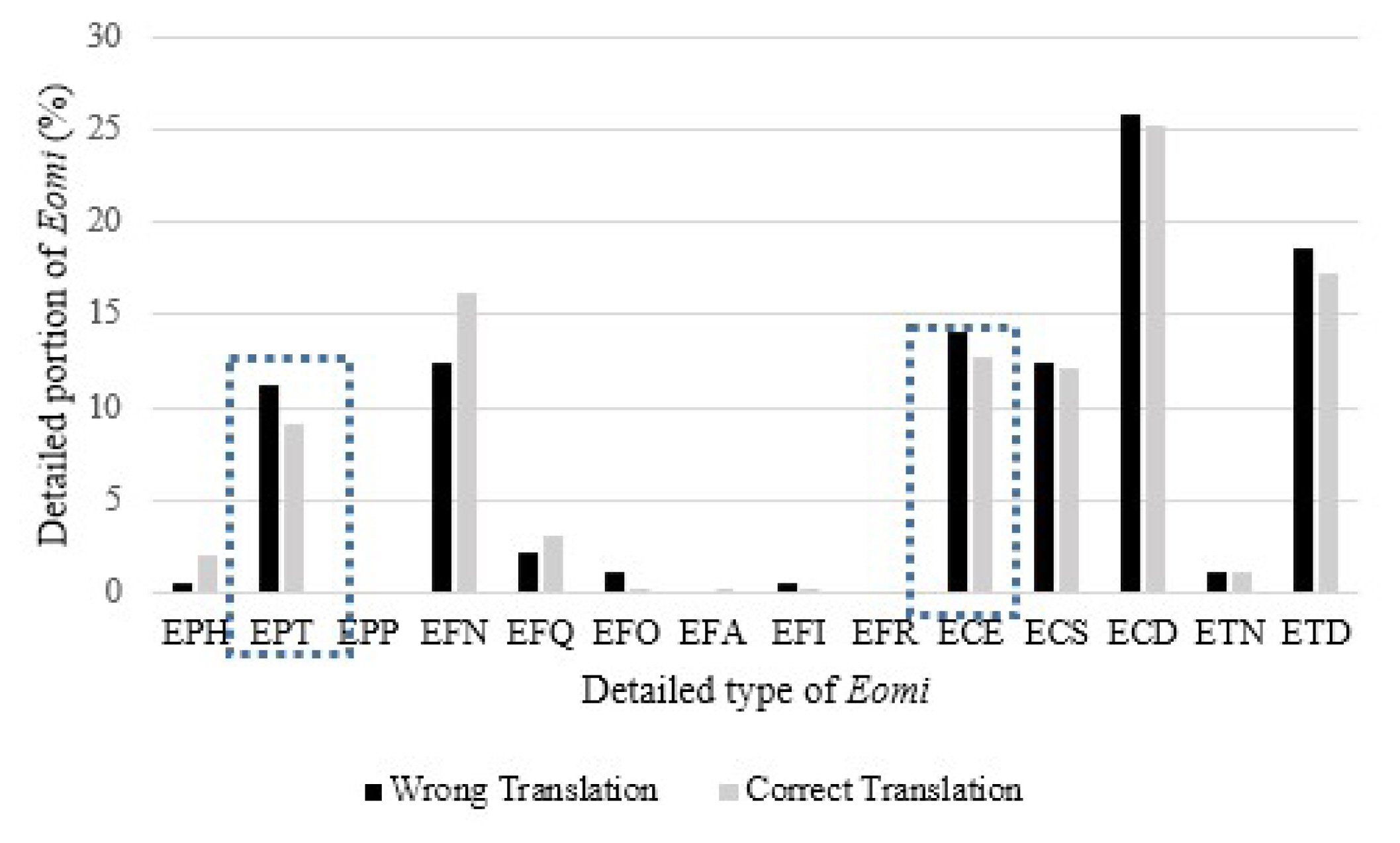

A Kokoma Korean morphological analyzer, one of the most necessary parts in natural language processing systems, is used. This is an open tool available for online use and as a downloadable application. The Kokoma Korean morphological analyzer tags the Korean script according to nouns, verbs, and adjectives. They were categorized into 45 groups by tagging the parts-of-speech: NNG, NNP, NNB, NNM, NR, NP, VV, VA, VXV, VXA, VCP, VCN, MDN, MDT, MAG, MAC, IC, JKS, JKC, JKG, JKO, JKM, JKI, JKQ, JC, JX, EPH, EPT, EPP, EFN, EFQ, EFO, EFA, EFI, EFR, ECE, ECS, ECD, ETN, ETD, XPN, XPV, XSN, XSV, XSA, and XR. This categorization includes nine subsets in josa and 14 in eomi, which are counted in each sentence. The data reveal which ones are the most frequent and the least frequent in English and Korean. In this study, all punctuations were removed from the data1.

The subtitles are scored by Korean American bilinguals. The scores were graded from “most corrected” (5 points) to “least corrected” (1 point), with points 5-3 indicating correct translation and points 2-1 as wrong translations. Although the subtitles are grammatically wrong or awkward, if they are understandable and usable in an informal situation, the subtitles are grouped into over three points. The least corrected of the two groups that have point 1 and 2 scores are analyzed to determine which POS has the most common errors.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print